Why I came to New Orleans

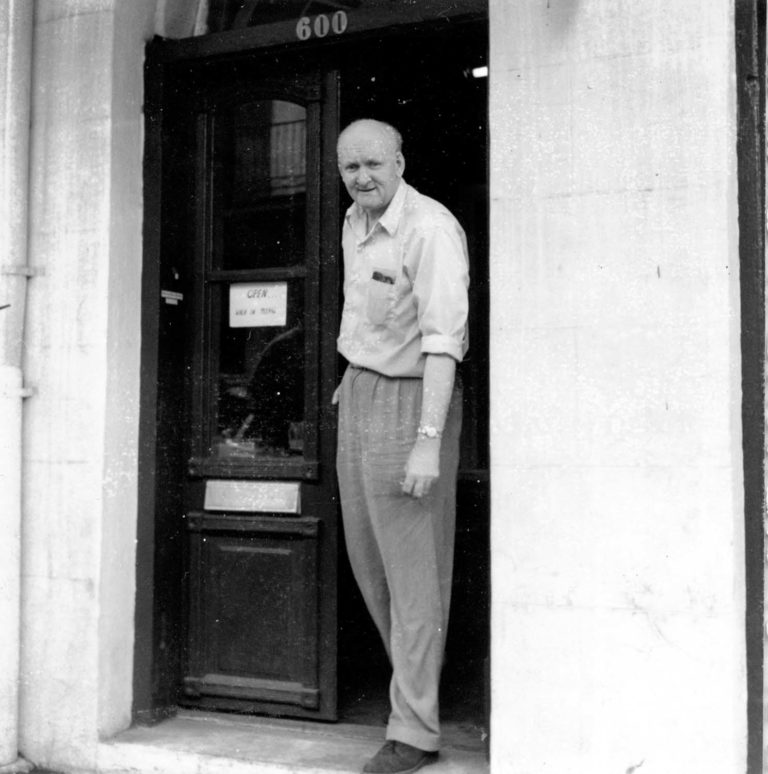

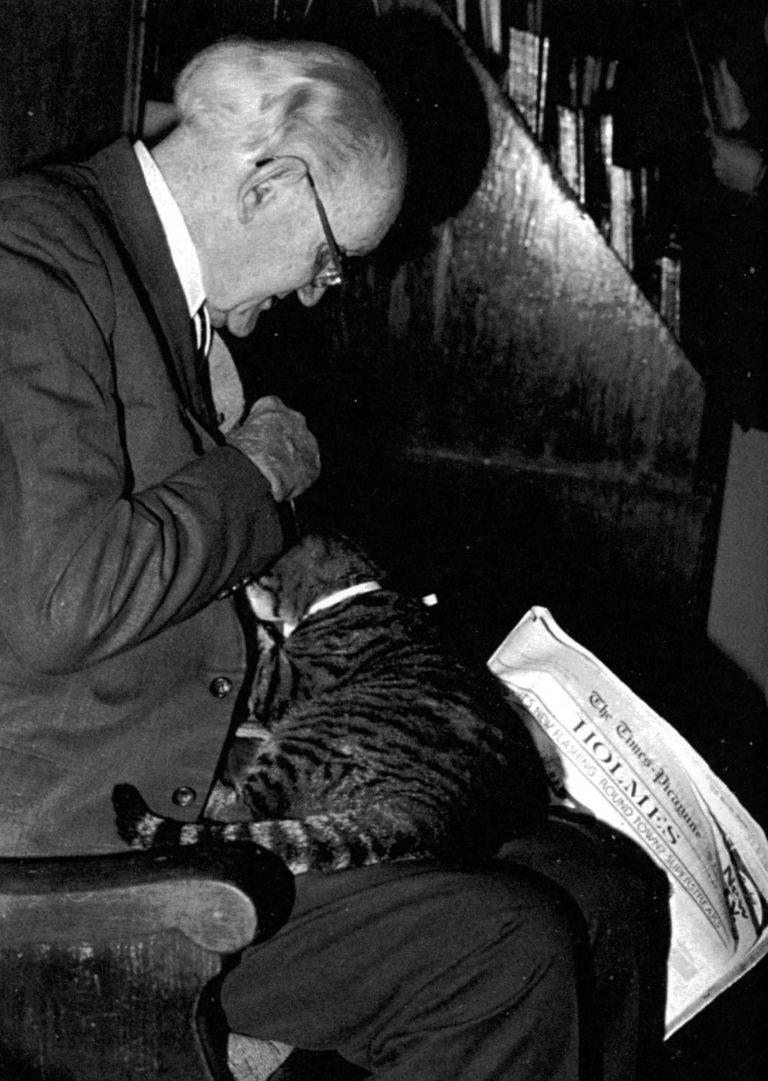

Bill Russell in his apartment on Orleans St. “Bill Russell, 75, jazz studies patriarch, works in an office cluttered with jazz documentation” From Smithsonian Magazine, Nov. 1980. Photo by Enrico Ferorelli.

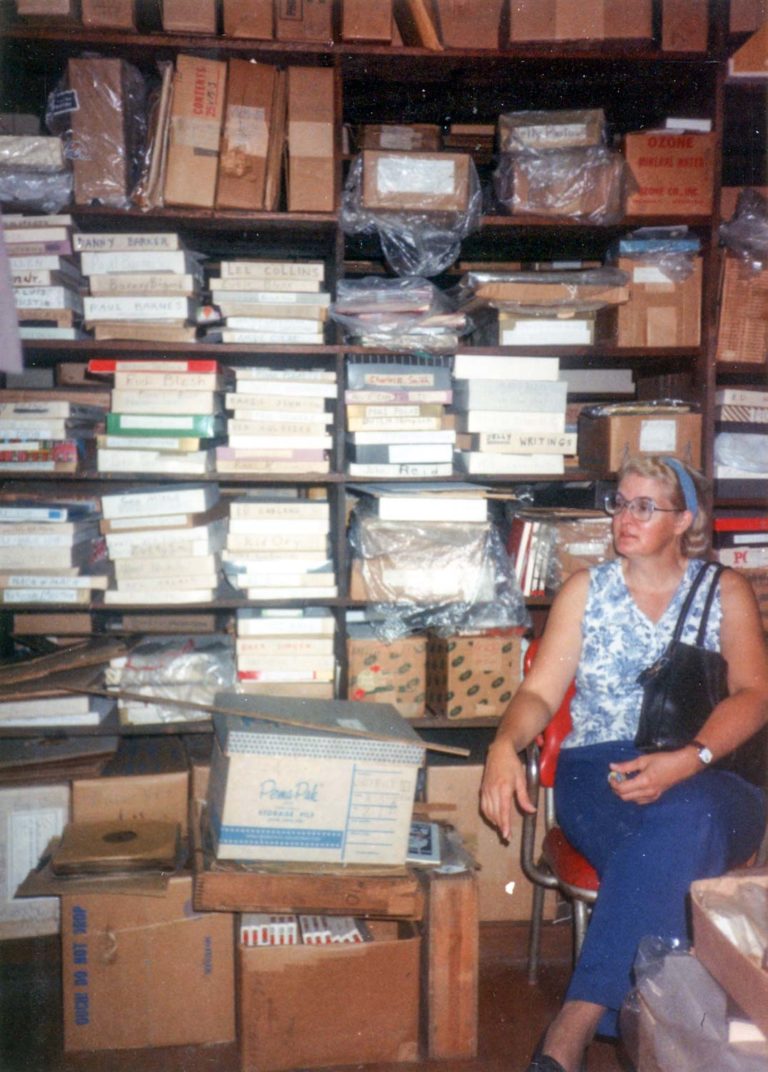

This was his “bedroom” (the bed was on the far right wall in the corner. the room behind was the kitchen. The entire apartment was filled to the ceiling with papers and books and instruments and photos about Jazz. It was a living archive and he knew where every scrap was. At his death the collection was sold to the Historic New Orleans Collection where it is available for research. This photo was used in a magazine article about him.

Growing up, he was just my “Uncle Russell” (his real name was William Russell Wagner). I didn’t know then that he was one of Dixieland Jazz’s leading authorities and a composer, or that he was good friends with Louis Armstrong and John Cage. I didn’t know who Mahalia Jackson was and that he was her manager. He was just my crazy uncle who bet me a dollar I couldn’t play Mary Had A Little Lamb on the cello, knowing full well I could. He had a sly and caustic sense of humor that not everyone got. But he always had a twinkle in his eye and a boundless energy.

In my late teens, I remember going down to New Orleans to visit him in his French Quarter apartment packed to the 12-foot ceilings with boxes of papers and photos, musical instruments and vinyl records. He’d take us to all the best places – his favorite oyster bar, the Cabildo, and of course, Preservation Hall. He’d sit in the breezeway on a tall wooden stool and sell records and everyone knew him. People from Germany and Sweden and England would joyfully greet him like they were old friends, and he always had a story to tell.

“Russell was the single most influential figure in the revival of New Orleans jazz that began in the 1940s.” The Times

Bill Russell was one of the leading authorities on early New Orleans jazz. He knew Louis Armstrong personally, and was Mahalia Jackson’s manager for many years. He authored articles and books, including three essays in the book, Jazzmen and the 720-page Jelly Roll Morton scrapbook, Oh, Mister Jelly.

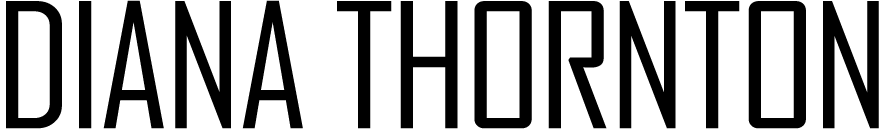

TO BILL RUSSELL, MY MAN. BEST WISHES, LOUIS ARMSTRONG. Bill Russell, Lavonne Tagge, Louis Armstrong and George Tagge at the Blue Note, Chicago, November 29, 1954. The Taggs were jazz fans who corrsponded frequently with Russell. From New Orleans Historic Collection/Jazz Scrapbook

Russell founded American Music Records, which helped bring many forgotten New Orleans performers, including Bunk Johnson, back to public attention. My mom remembers when she was a child during WWII he lived with them in Pittsburgh and made records in their attic. He was key in Bunk Johnson’s revival and he recorded Johnson on his American Music label.

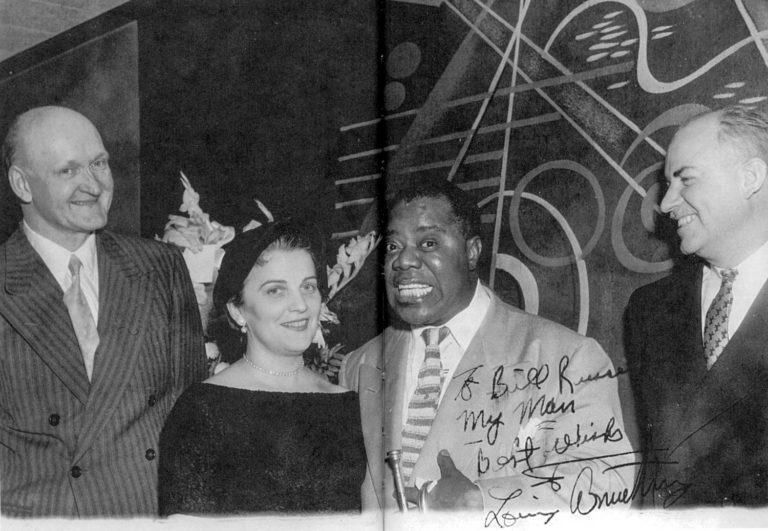

Russell Wagner, Bunk recording session. “A Bad Night,” according to Russell’s note. Bill Russell and Alfred Lion recording at San Jacinto Hall, a well-known jazz site on Dumaine Street, August 1944.

Bill Russell and Alfred Lion working with recording equipment at San Jacinto Hall, August 5, 1944. Photo by Wm. Wagner. From Southern Quarterly, Winter 1998

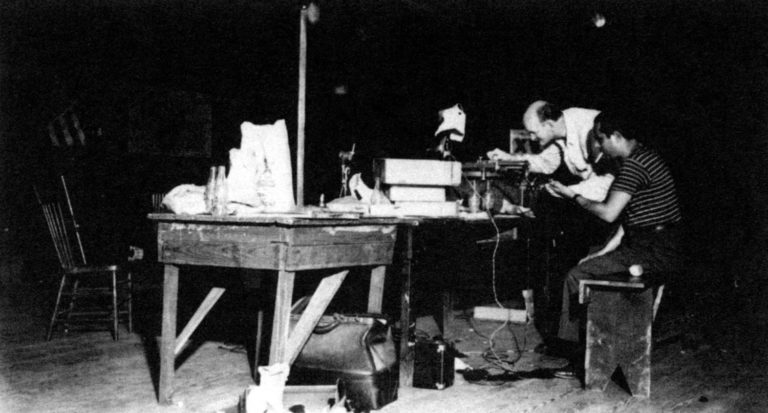

He moved to New Orleans in 1956, settling in the French Quarter where he opened a small record shop at 600 Chartres Street, repaired violins and quickly became a part of the fabric of New Orleans.

Bill Russell at his record shop at 600 Chartres St., French Quarter, New Orleans, LA.. June 1957. Note sign: Open…walk in please.

Russell also played violin with the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra. In 1958, Russell co-founded and became the first curator of The Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University and was there at the birth of Preservation Hall. He was a fixture in the breezeway nearly every night as “the kindly bouncer” selling records, chatting up the patrons, usually with a cat on his lap.

Bill Russell with cat at entrance to Preservation Hall, April 1978. From New Orleans Historic Collection/Jazz Scrapbook

Russell amassed a huge collection of material related to the history of New Orleans, early jazz, ragtime, blues, and gospel music, all of which he kept in his French Quarter apartment. At his death in 1992, he left his collection to The Historic New Orleans Collection, where it continues to be a valuable resource for researchers.

Lois Thornton at Bill Russell’s Orleans Ave. apartment, 1990. In front room

Bill Russell was also a leading figure in percussion music composition, influenced by his acquaintances John Cage and Henry Cowell. Russell likewise influenced Cage in his emphasis of percussion. During the 1930s Russell’s percussion works called for “instruments” such as Jack Daniels bottles, suitcases, and Haitian drums, as well as “prepared pianos”, although it is not clear how specifically he wanted the piano to be prepared.

In 1989 I moved to New Orleans “temporarily” to be near my uncle for the last years of his life. I never planned on staying, but New Orleans had different plans for me.